Narrowboat handling, like all boat handling is simple in principal, but you would be amazed at how many individuals struggle with the basics. I’ve often compared driving or steering a narrowboat to manoeuvring an articulated lorry from the back, with no brakes. What I’ve tried to do here, without lecturing too much, is to outline some good practices for boaters new and inexperienced who want a few guidelines on cruising on the canals while sitting in their armchairs! There are a few good narrowboat handling courses available around the UK, and there is absolutely no substitute for hands on experience.

Starting the engine.

Before you turn the ignition key, ensure that the throttle is in neutral. This is usually achieved by pulling out the short lever on the Morse control to disengage the gearbox, and will allow you to open the throttle a little.

Turning the key to the interim setting allows the glow plugs to warm up (this can take between ten and thirty seconds depending on your boat, and is usually accompanied by a blue or yellow ‘preheat’ light on your control panel, and in some cases an audible warning) before finally turning the engine over on the starter. Make sure you allow the engine to warm up for a few minutes before you move off.

Untie both your fore and aft mooring ropes – I usually leave the aft tied until last to avoid the rear of the boat drifting away from the bank. Make sure your ropes don’t fall into the water as it is only too easy for them get caught in the propeller, and don’t forget to put your mooring pins and mallet away securely. Take a quick glance to see that you won’t be pushing out in front of any approaching boat traffic then gently push the boat away from the bank. Pushing the front away first will make the boat’s rear rotate towards the bank, helping you step on, but make sure you don’t foul the prop in shallow water. If the water is particularly shallow, push the back of the boat out, reverse away first until there’s room to straighten up, and then engage forward gear.

Once you have straightened the boat out, engage forward gear and accelerate gently to cruising speed. On all waterways, you should drive on the right, that is, you pass approaching boats port side to port side (effectively the opposite to driving in the UK). In practice, on most canals, you’ll keep to the centre of the channel – it’s shallow near the edges – unless there’s another boat coming towards you. You should also slow down when passing anglers and other boats.

Steering a narrowboat

Most narrowboats have tiller steering which is fairly simple – just as long as you remember that pushing to the right will make the boat head left and vice versa. Don’t rush your manoeuvres and plan ahead – the boat will take a few seconds to respond. Your boat will rotate from a point about halfway along its length. That means you need to keep watch out for the front and the back of the vessel.

If you line up the front only and then try to turn into a narrow gap – a bridge or lock, for example – you run the risk of hitting the side with the back of your boat.

Some cabin cruisers or wide beam vessels have a ships wheel rather than a tiller. Steering a boat with a ships wheel is a bit more like steering a car, but it’s more difficult to judge where your wheel should be for going straight ahead. Get to know the feel of the wheel and the rudder position before you set off. Some wheels have a centre point marked for the purposes of indicating the ‘straight ahead’ setting.

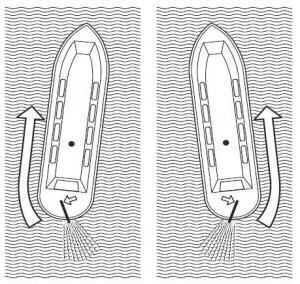

Reversing in a narrowboat

This is what really separates the men from the boys! Unless you are blessed with bow thrusters, any narrowboat has a tendency to veer to one side or the other when in reverse. Usually, you will find that there is an optimum speed in reverse where the boat becomes fairly steady. If the narrowboat is drifting offline, it can sometimes be corrected by a to-ing and fro-ing of the tiller (almost creating a rowing action) to bring the boat back online. Undertake any manoeuvre in plenty of time, and as smoothly as possible.

Negotiating Tunnels

There are some tunnels on the UK canal network that take 45 minutes or so to negotiate. Most tunnels drip with water, so be sure to don waterproofs before entering them. Trying to struggle into a Sou’wester while steering a boat in the dark is no joke. Tunnels can be narrow with only room for one-way traffic, or they can be wide enough for two boats to pass. Virtually all tunnels have a board at their entrance with specific contact instructions, such as entry times or cruising restrictions. Some even have traffic lights at the tunnel entrance. If it’s a one-way tunnel, without any obvious right of way indicated, make sure there’s no boat inside. Switch on your headlight and some interior lights. For the best vision, try and invest in a broad beam headlight to illuminate the tunnel roof about 50 to 100 yards ahead. Some stern lighting will help a following boat to see you, but if it’s a single bright spot or rear navigation light, it may be confused with a headlight by the helmsman of a following boat.

Remember – don’t turn your headlight off until you emerge fully from the tunnel. You may be able to see adequately for the last 100 yards of so when leaving a tunnel, but to any approaching narrowboat, you will be in pitch darkness and virtually invisible.

It is best to steer by remaining in the centre of the tunnel, moving to one side when passing approaching craft and keeping to a moderate speed. Move the tiller or wheel as little as possible – it’s a common illusion to feel the boat’s being pulled to the side. Watch out for the changing shape of the tunnel. They are rarely straight and may vary considerably in headroom. Keep at least two minutes (at normal cruising speed) or about 200 yards away from any boat in front of you.