How far can narrow boaters cruise in a day? This frequently asked question can cause all sorts of consternation on a narrow boat – and it is often one of the hardest to answer!

A great deal depends upon the narrowboat crew. Many boat crews like to be up and about early, but as many other narrowboaters are relaxed about when they cruise – relying on the state of the weather conditions, rather than what time of day it is.

As a result, a number of things will determine how far boats can travel. There is, however, a relatively simple method of calculating how far you can get in a given period of time. If you remember that, on canals, your boat is not allowed to travel at more than four miles per hour, and if you allow a quarter of an hour for passing through each lock, then:

1 mile = 1/4 hour = l lock

So to determine the time taken for any journey, simply add the number of locks to the number of miles and divide by four.

The speed limit on canals is four miles an hour. This is a fast walking pace and is the absolute maximum – remember – it is a limit – not a target!

The speed limit on canals is four miles an hour. This is a fast walking pace and is the absolute maximum – remember – it is a limit – not a target!

Most narrow boat cruising will be around three miles an hour, or less. Moored boats, shallow water or congested and narrow sections of canal all mean that narrowboat crews will have to slow down. If more boaters made a habit of glancing behind them to check on the wash their narrow boat makes, they would immediately see if they were going too fast. A general rule of thumb is – if you are making waves you are going too fast.

Heavy wash not only causes damage to banks, but can wash debris into the water. Apart from increasing the risk of debris becoming caught around your prop and stern gear, it can also cause considerable discomfort and even damage to moored boats.

If you are going too fast for the prevailing conditions, there is a real risk of tearing out the mooring pins of moored boats. I have seen apparently securely moored boats that have drifted right across the canals width, simply because a previous boat had not slowed sufficiently before passing. And that is an important point to remember. You need to lower your speed before you reach moored boats, not when you reach them as the momentum of water your boat is displacing will still create a towing effect if you have not slowed early enough.

Some boaters have the unfortunate attitude that if your pins came out when they pass in their boat, then you couldn’t have tied yours up securely. This is both selfish and arrogant. There will be odd occasions when a poorly moored boat may drift away from the bank due to the ground being exceptionally soft, but when this happens, the most courteous thing is to pull into the bank, pull the boat back to the side and just bang the pins in again.

On the subject of mooring, there are a number of different methods of securing your boat to a variety of materials. Broadly speaking, the towpath side of the canal is the accepted mooring side, provided there are no restrictions or limitations present. The towpath may be furnished with mooring bollards or mooring rings in designated mooring areas. Do NOT moor on the bollards approaching a lock – they are there for passing traffic ONLY. Alternatively, the canal bank may be lined with Armco – vertical, corrugated metal plates bound by a horizontal rail.

You can tie to these using Armco Pins or alternatively a mooring chain. Don’t be tempted to loop your mooring rope around the Armco, as the constant movement of your boat could cause the rope to fray or even get cut through.

Now, I wish I could say obviously, but under no circumstances should your mooring ropes cross the towpath. This is extremely dangerous to any passing traffic, be it on foot or bicycle – and ensure that your mooring pins are clearly visible to other canal users.

There are some snazzy, luminous pin covers on the market (I even made a pair from an old, reflective hi-visibility jacket) but at the very least, make the pin position stand out by tying a white cloth or carrier bag around it. You can also use old washing up bottles (usually already white or yellow) with a slot cut down its length and pushed over the pin.

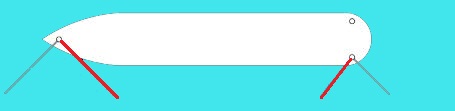

Finally, anyone who has moored out on the cut for any length of time will appreciate the benefit of ‘springing’ their ropes to reduce fore and aft movements. Springing mooring ropes is a way to reduce the boat being dragged to and fro as other boats pass (or water is let out of locks rapidly).

Put simply, additional mooring ropes are taken from the fore and aft T studs on the boat and attached to a second set of mooring pins hammered into the bank (see the diagram below). These two additional ropes (marked in red on the diagram) should form a near right angle to the originals. By doing this, the vessel is now able to resist water flow in either direction.

Many boaters also adopt this method of mooring where the towpath is particularly soft (perhaps caused by flooding or heavy rain) as the additional mooring points help to spread the boats load more evenly.

Many boaters also adopt this method of mooring where the towpath is particularly soft (perhaps caused by flooding or heavy rain) as the additional mooring points help to spread the boats load more evenly.

One last point – should you find yourself having to moor where water levels are likely to fluctuate (such as on tidal rivers for example), remember to check your mooring lines regularly. Rising water levels have been known to pull out mooring pins, and boats tied tightly to bollards run the risk of tilting to the point of capsizing. If you can, run your mooring lines through a ring and attach the free end back to the boat. That way, you can loosen the lines without having to try and get ashore….